Though tax avoidance isn’t illegal, it is certainly

unethical. It is in this grey area of uncertainty that tax avoidance exists and

it is this uncertainty that exploits it. So the question is, avoiding tax might

be legal, but can it ever be ethical? At times where governmental spending cuts

have a real impact upon the every lives of people, it does confuse me as to how

multinational firms would avoid paying their fair share of taxes like the rest

of us. Avoiding tax is avoiding a social obligation and it is in the greed of

businesses, which damage its reputation.

In a recent story, McDonald’s is currently facing

fines as part of the European union initiative to stop tax avoidance in Europe.

Unsurprisingly, US officials are accusing the EU for picking up on American

companies rather than their European rivals. Forgive me but is America even

part of the EU? The cheek.

In today’s global environment, it seems as though

companies are intoxicated by this idea of shareholder value maximisation. With

this, it is in their best interest to make as much profit as possible through

diving through the nearest loophole in tax avoidance. Don’t get me wrong, from

a purely business point of view, why wouldn’t you to save money. Through doing

so, this would provide your business with a tax advantage, saving much money,

which can be reinvested back into the business. After all, it is in the

government’s failures, which are being exploited.

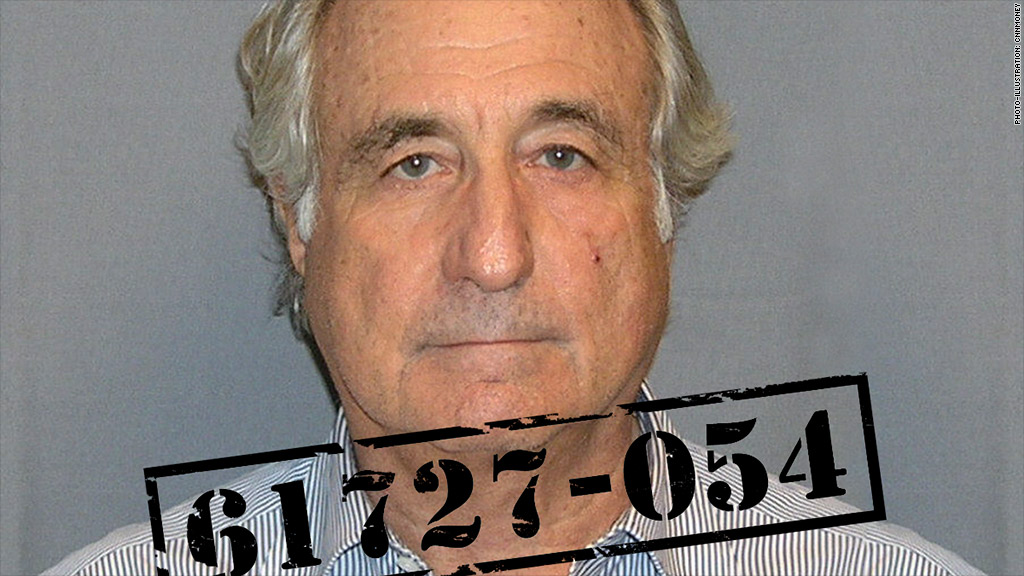

Just to be clear, I’m not defending tax evasion, which

should be stopped and prosecuted for. The point of my argument is that tax

avoidance happens everyday. Have you ever bought something from the airport

that was ‘tax free’? Essentially, this is also tax avoidance although is

considered perfectly acceptable. I guess in reality it depends upon the scale

of the damage.

Rather than hiding from tax avoidance, both the

governments and companies need to be transparent about tax negotiations and the

stance on the law. Through doing so, this would to an extent, restore some

public trust.